Multiple authors

We are excited to launch Eliminating Hepatitis C in Europe: Report on Policy Implementation for People Who Inject Drugs! The publication is part of C-EHRN’s Civil Society-led Monitoring of Harm Reduction In Europe 2023 Data Report and focuses on the availability of and access to interventions that constitute the HCV continuum of care specific for people who inject drugs.

The report analyzes data from 35 European cities, provided by civil society organisations designated as focal points within the C-EHRN network. It assesses the impact of national strategies on HCV testing and treatment accessibility for people who inject drugs, examines the continuum of care across countries and cities, explores changes in the continuum of services over time, and highlights the role of harm reduction services in this context.

We asked Tuukka Tammi, programme director at the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare and the primary author about the findings and how harm reduction organisations can use the report to advocate for their work at a city level. Download the report and read the interview below!

People who inject drugs are the main target group, if we use these words, for hepatitis C -related work. I don’t think that in any country only the specialized infectious experts could do enough in contacting, finding, treating them and keeping them in the treatment system.

Harm reduction services, services for the unhoused and all these low-threshold services are the only places where many of the people who use drugs are met, not anywhere else. This is also the case in Helsinki, where I come from. Even if we have quite a good general health care, many of the people who are hepatitis C positive don’t ever go there for one reason or the other. So I think harm reduction organisations are necessary partners for the healthcare system and infectious disease experts.

The hepatitis C testing & treatment guidelines are part of the questionnaire and the idea is to see the progress on the formal side of things. To be successful in hepatitis C work with people who use drugs, the country or the city needs to have formal guidelines so that these people are treated in a uniform way in different clinics. But we know that formal guidelines or instructions do not yet mean that the same happens in practice. So we also asked if they see contradictions or limited impact in practice.

Respondents reported many kinds of real-life impacts of these guidelines for testing and treatment and other services for people who use drugs. Mostly they say that these have a positive impact. They make hepatitis C-related work better in many ways, meaning people have better access to treatment and testing, and other positive impacts. Some mentioned that civil society organisations have better access to work with hepatitis C or are more involved because of the guidelines if these have an emphasis that low threshold services like harm reduction services should be included in the work.

Respondents from three cities from Eastern Europe believe that the guidelines had a negative impact. This mainly has to do, I think, with stressing in the guidelines that all hepatitis C-positive people need to be treated in specialized healthcare. We know it would be important to include harm reduction services in this work because people who inject drugs are often marginalized, often unhoused, and do not usually go to these specialised public healthcare settings.

One repeated missing thing was that undocumented migrants are not included in the guidelines. In practice, in many cities, there is no access to any testing or treatment services for them.

At the very general level, the interpretation from the past 4 years was that there is some positive development and also that this positive trajectory has been reestablished after the pandemic when the situation in many places got worse because of restricted opening hours and moving from face-to-face clinical work to some other forms of work.

Also on a very general level, it can be said that there is polarisation of European cities. In many cities, it seems that they are proceeding quite well and might even reach the global elimination goal for 2030, to eliminate hepatitis C totally or almost totally. Then there are cities where the progress is very slow and there’s a lack of many things like economic and political support for this work or advocacy, and insufficient infrastructure for testing and treatment in general. Some cities still have old-fashioned working methods, even the interferon treatment, which is not very effective and not very nice for the patient, but luckily this is quite rare.

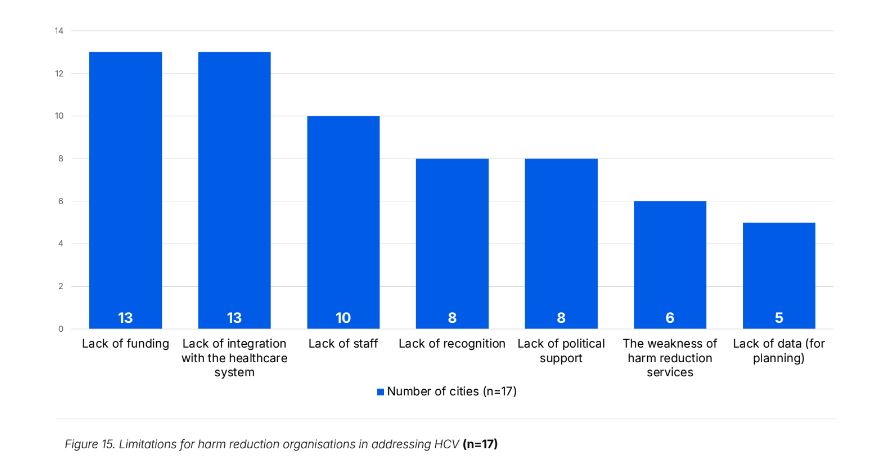

Number 15. I think this is one of the main graphs from the viewpoint of harm reduction-related work, what kind of limitations are there for harm reduction organisations in addressing hepatitis C? This has been a more or less similar graph for many years. We see that there are 2 main obstacles: lack of funding and also lack of integration with the healthcare system. That’s a resource problem and a structural problem, not having links and connections.

10 cities mentioned a lack of staff doing testing and treatment, extra work in addition to other work they do. Then maybe the lack of recognition is related to the lack of integration with the healthcare system. Not everywhere are the harm reduction organisations regarded as relevant or qualified partners for doing this work. On the same level is a lack of political support, and there is a general weakness of local harm reduction services, they don’t have capacities to do this work. A lack of data for planning the work was also mentioned.

I think if we turn this into an advocacy or planning language, these are also the same factors that would need to be paid attention to.

There surely are good practices and good examples from many cities, how they are very well integrated, such as in Amsterdam, or in Barcelona where they also have an observatory for monitoring stigma in services.

The lack of funding and lack of political support is a more tricky one. It varies a lot, how the funding works in different cities. We know that for instance, in many Eastern European countries, there’s a general lack of or no funding for harm reduction services more generally, not only related to hepatitis C work.

One way to use it is to compare their situation with the others. If it’s worse than in other cities, making some noise about it in their cities and countries would be useful. Comparing different situations can also be an effective way to talk to policymakers. Not naming and shaming, but showing that harm reduction organisations can be very effective partners for the healthcare system in reaching people with hepatitis C and providing testing and treatment to them because we know that the prevalence of hepatitis C is most common among people who inject drugs and these people are not usually very well reached by the public healthcare system. So showing that this is possible, also in old fashioned systems where they still doubt that harm reduction organisations would be able to do this, showing from the example of other places that it’s working fine.

This report is hopefully useful for peer learning for some people. The more open and qualitative narratives in the report tell how things work in practice in different cities, which could be a source of inspiration for others. They could see what is happening in other cities and contact their colleagues from those cities to ask them for more detailed information: how does it work and how did they succeed in getting it done in the first place.

Following a new format, Correlation – European Harm Reduction Network’s Civil Society-led Monitoring of Harm Reduction in Europe 2023 Data Report is launched in 6 volumes: Hepatitis C Care, Essential Harm Reduction Services, New Drug Trends, Mental Health of Harm Reduction Staff, TEDI Reports and City Reports (Warsaw, Bălţi, Esch-sur-Alzette, London, Amsterdam). The Executive Summary can be accessed here.