During the 3rd day of the INHSU 2022 conference, Roberto Perez Gayo, policy officer of C-EHRN, chaired a session on the need for scaling up community-based HCV prevention, treatment and linkage to care services for people who use drugs.

Tessa Windelinckx of the Free Clinic in Belgium outlined their work and stressed that the clinical component of their programme was dependent upon their peer outreach workers and, therefore, collaboration between medical staff – including doctors and nurses – and peers was vital to reaching the most vulnerable people with viral hepatitis C (HCV) services and to link them with care. In addition, each part of the Free Clinic portfolio of services benefited from having staff with varying experiences working together, such as those running the needle-syringe programme (NSP).

As most vulnerable people are afraid of government services due to the stigma and discrimination that is often prevalent by such healthcare staff, peer-to-peer support by Free Clinic – called C-Buddies – acts as a bridge, or facilitation mechanism, between those in the community and the service providers at Free Clinic fixed sites. C-Buddies are usually people from the vulnerable community who use communication methods to build friendships with vulnerable people within a stable environment. Through building trust, vulnerable people are encouraged to access a range of services offered by Free Clinic, including HCV testing.

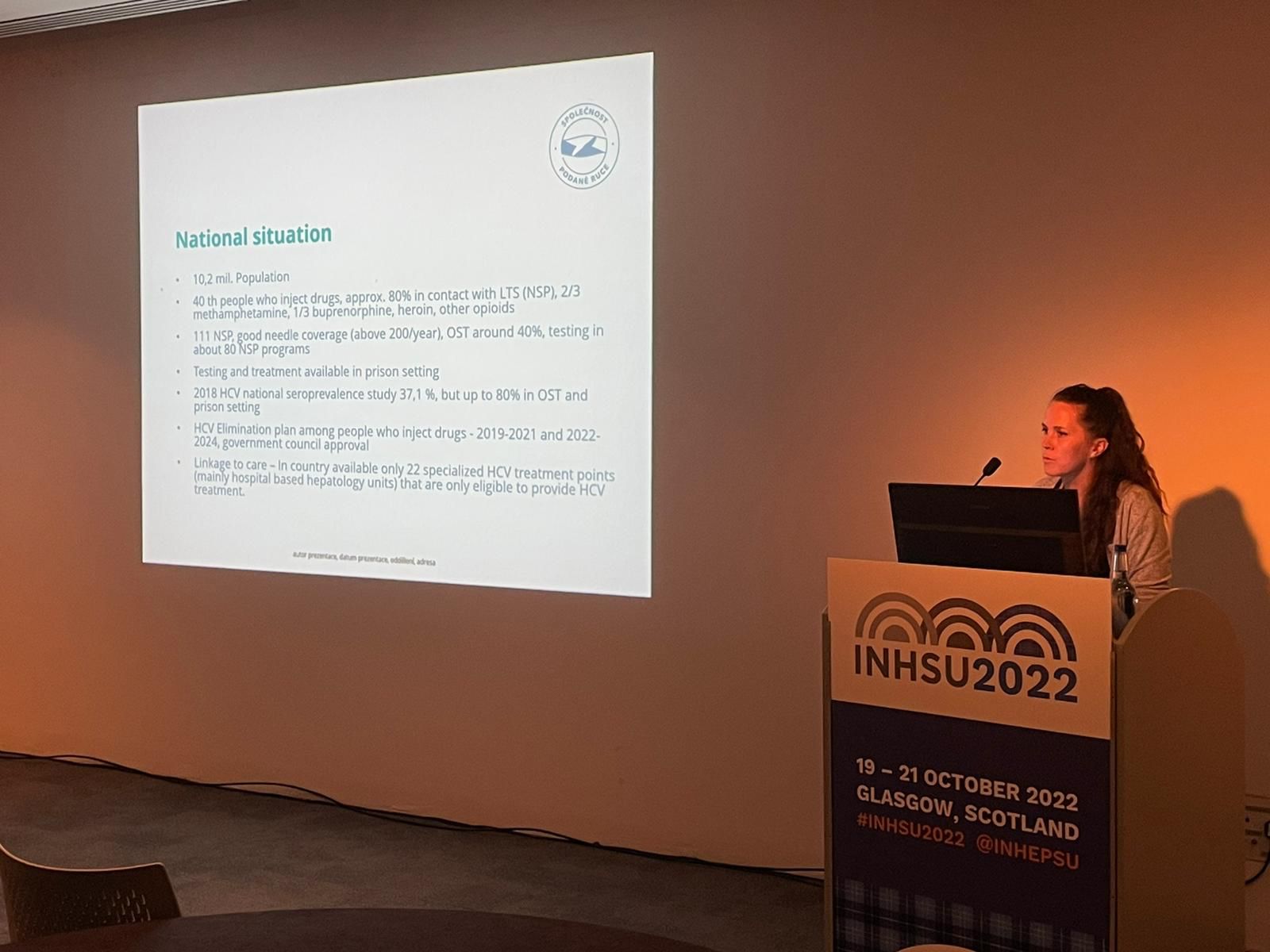

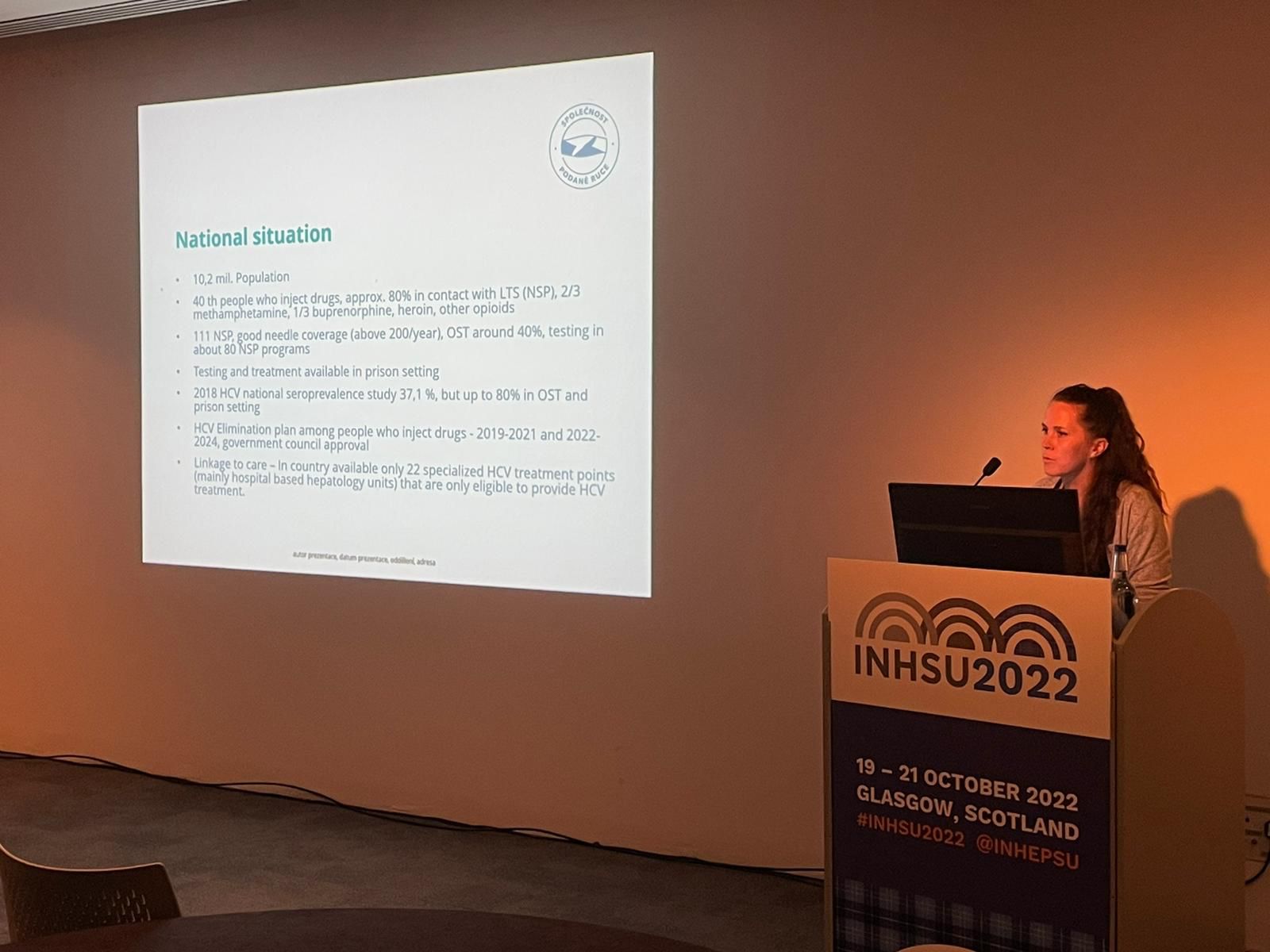

Lucie Maskova of the Spolecnost Podane Ruce non-governmental organisation (NGO) in the Czech Republic (Czechia) provided information on their services, noting that the country had an HCV elimination plan for people who inject drugs, but that treatment was only available through 22 specialised centres throughout the Czech Republic rather than through NGOs or other mechanisms. Rapid HCV testing through a finger-prick, or a sample of saliva, is facilitated through drop-in and mobile/outreach services as well as part of providing opioid agonist therapy (OAT) and drug treatment and includes counselling by non-medical staff. Approximately 2,000 people each year are tested for HCV. HCV testing is also provided for refugees from Ukraine with trained peers who speak Ukrainian and Russian.

Recently, an infectious disease specialist joined the NGO who will hopefully be able to prescribe direct acting antiviral (DAA) medication in the near future. Challenges facing the NGO include how to address comorbidities and the limited number of trained peers, together with funding as well as the relatively limited number of centres where DAA’s are available; the country also needs a national coordinator for the HCV elimination efforts.

Read the full presentation here.

Examples of service provision in Italy were presented by Nadia Gasbarrini of the organisation Fondazione Villa Maraini which was founded in 1976 and delivers low threshold services including an emergency unit, drop-in centre, night shelter and services inside prison as well as outreach on the street. OAT, HIV and HCV services are also available, plus higher threshold interventions, including a therapeutic community and outpatient treatment.

On-site and street-based HIV and HCV testing and linkage to care also provide counselling, psychological support – including support to families – as well as peer-to-peer education and, more recently, COVID-19 testing and screening [see images 9 and 10]. In addition to people who use drugs, sex workers, the LGBTQI+ community, the homeless and migrants are also served. However, treatment of HCV involves referral of individuals to a hospital rather than provision of DAA’s through the organisation. To-date, in 2002 there were 536 people tested for HCV. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, the number of people tested was 1,310.

Read the full presentation here.

Group Discussion

Following the presentation, participants joined a group discussion. The key points include:

- Important to include harm reduction as part of the medical training curriculum and to provide medical students with internships to work with organisations delivering harm reduction services as part of improving their practical skills in the delivery of client-centred harm reduction services;

- Crucially, peer training of public-facing staff at healthcare facilities is important as receptionists and security guards are the first people with whom a vulnerable person will come into contact with.

- Legislators/regulators should improve their understanding of how harm reduction services are delivered and be more flexible in the regulations and guidelines used by the medical profession in the provision of standard interventions for people who inject drugs and other vulnerable people. Likewise, harm reduction advocates need to facilitate awareness raising by legislators/regulators of the opportunities to make services more flexible and adaptable to the needs of vulnerable people;

- Staff turnover is a challenge within organisations and there is a need to increase the number of peers trained in the delivery of an integrated approach to the provision of health, social and economic support interventions, including housing. It is also vital that trained peers are paid properly for the skills that they provide to service delivery agencies and are not discriminated against by being treated as volunteers due to their prior, or ongoing, lived experience;

- The role of trained and trusted peers is vital as most vulnerable people are suspicious of healthcare workers. Therefore, outreach supports vulnerable people, such as providing evidence-based and clear information; answering questions; accompanying individuals, if needed, to healthcare facilities and acting as a bridge for both the client and healthcare staff to communicate and benefit from the available services; and to provide other pathways for a vulnerable person to voluntarily access social and economic services;

- The time available for a doctor to spend with an individual client can be very limited due to the number of people seeking assistance and other competing priorities. Therefore, where practical, task shifting should be used to allow nurses and others to perform a range of tasks as this will free up time for a doctor to focus on those people who have more complex health and related needs;

- There is a need to integrate services as the opportunities for the individual to return to a service provider could be extremely limited. Therefore, testing for common communicable diseases should be undertaken at the same and, ideally, for results to be available immediately that allows for treatment to begin without delay; this will reduce loss-to-follow-up and allow the client the most pragmatic approach to improving their health. However, at present, many providers –especially for OAT – have different regulations that they follow. Service providers need to show flexibility to improve access and adherence to treatment by vulnerable clients;

- In running an effective harm reduction organisation, it is necessary to strike a balance between good levels of peer supervision and avoiding unnecessary meetings or paperwork. In addition, services must not try to micromanage vulnerable individuals as this will likely lead to them not returning again;

- Good linkages with local law enforcement is important in facilitating access by vulnerable people to harm reduction services, either at fixed sites or through outreach. Examples from Tijuana, Mexico, were given during the Conference as to how this can be undertaken. Such linkages with police can be either formal or informal in nature but with the same objective of facilitating access to services by vulnerable people in the community. Small steps, such as peer education for police, can be the start of the process that eventually culminates in decriminalisation;

- Different agencies of the same government structure can work against each other in reality, such as a health department supporting civil society partners to provide HCV testing in the community but the local laboratory being a barrier to PCR confirmatory testing; funding can also reflect the different priorities of government agencies;

- Telehealth can increasingly link clinical providers with vulnerable people as a way of helping clients feel easier about accessing health services;

- Stigma remains a major barrier to increasing access to, and full utilisation of, health services by vulnerable people.

Summary

In conclusion, participants stated that the most important issues for service providers to consider in establishing and scaling-up community-based HCV prevention, treatment and linkage to care services for people who inject drugs include:

- Gaining the trust of people who inject drugs which can be achieved through trained peers who are paid at the same levels as those without such lived or living experience of drug use;

- Ask people who inject drugs what they want; do not make assumptions on their behalf;

- Ensure you have a baseline at the beginning of service delivery so that you can calculate changes and impact over time;

- Learn from other organisations who have gone through similar processes and models of service delivery; this can include collaboration/partnerships with such agencies;

- Ensure that medical practitioners are given the opportunity to learn about harm reduction from people who inject and otherwise use drugs in order to adopt more flexible and pragmatic approaches to service provision; this could include internships while studying at medical school, for example;

- Provide access for people who inject drugs to education about the HCV continuum of care, including what medical practitioners require from those who undergo treatment, as well as barriers that clients may face in becoming free of HCV; and,

- Provide web-based information to organisations who are considering establishing HCV services for vulnerable people, such as the materials available from C-EHRN.